October 7, 2016

Mine Orer, Legal Intern, Koç University Law School Alumnus, and Oxford UN Human Rights Bodies Reporter

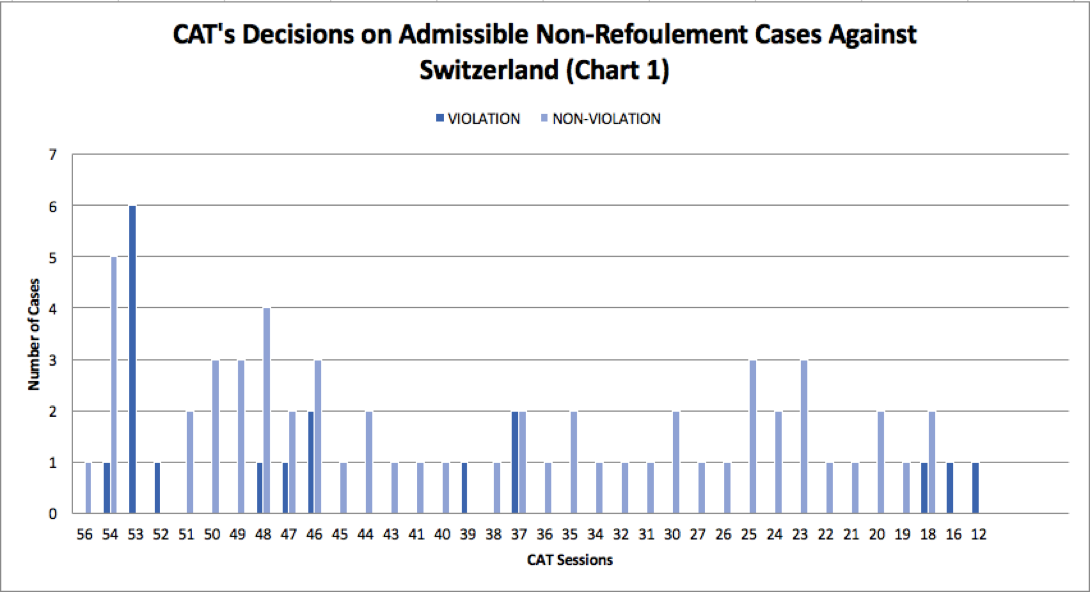

In this post, I will analyze the violation decisions given against Switzerland in the 53rd session of the Committee (03 Nov 2014 – 28 Nov 2014) regarding extraditions to Iran. With a total of 85 applications* since its accession to the Optional Protocol to the CAT, Switzerland is the recipient of the highest number of complaints before the Committee, all of them pertaining to the prohibition of non-refoulement. Of these 85 applications, 75 were declared admissible. Among the admissible complaints, however, only 18 were violation decisions, showing a good compliance rate by Switzerland with the CAT non-refoulement test.

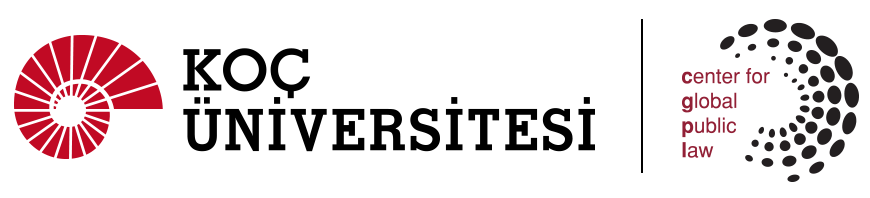

As seen on Chart 1 below, the Committee adopted the highest number of violation decisions against Switzerland in its 53rd session, which makes this very session an anomaly worth to be studied in order to understand the meaning of the “additional grounds” to the ones contained in Article 3(2). Also, because the Committee rarely gives violation decisions in general, the decisions analyzed below are indicative of how the Committee applies the principles contained in CAT Article 3 and General Comment no. 1 onto real-life cases.

The complaints against Switzerland that were reviewed in the 53rd session are X v. Switzerland, Khademi v. Switzerland, Tahmuresi v. Switzerland, Azizi v. Switzerland, Fadel v. Switzerland, and RS et al. v. Switzerland. The first four complaints are all pertaining to extradition of the complainant to Iran, whereas the other two involved extraditions to Yemen and Kosovo respectively. Given that the majority of the decisions were pertaining to extradition to Iran and all said decisions were violation decisions, they shall be the focus of this post.

The principle of non-refoulement, as outlined in Article 3 of the Convention against Torture (CAT), stipulates that a country is under the obligation not to deport or extradite someone if he or she runs the risk of being tortured upon return to the country of origin (note that the Refugee Convention further applies non-refoulement to persecution). The second paragraph of Article 3 of CAT specifically states that competent authorities will take into consideration factors “including the existence in the State concerned of a consistent pattern of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rights” when taking deportation or extradition decisions. The Committee Against Torture’s General Comment No. 1 further elaborates that the risk of torture does not have to be highly probable, but it must go beyond mere theory or suspicion. General Comment 1 also states that the burden of proof normally falls on the complainant, who must present an arguable case establishing that he runs a foreseeable, real and personal risk of torture. The Committee formulates this test as follows:

“the existence of a pattern of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rights in a country does not as such constitute sufficient reason for determining that a particular person would be in danger of being subjected to torture on return to that country; additional grounds must be adduced to show that the individual concerned would be personally at risk. Conversely, the absence of a consistent pattern of flagrant violations of human rights does not mean that a person might not be subjected to torture in his or her specific circumstances”

This dictum can be found in almost all of the Committee’s non-refoulement decisions. Despite the apparent clarity of the effect of Article 3(2) on non-refoulement assessments, the case law of the Committee can at times be puzzling. The Committee is often very clear with respect to which claims are insufficient to show foreseeable, real and personal risk of torture. It is not as clear, however, when it comes to what exactly the complainants must provide for their claims to be accepted. Thus, in order to understand what the Committee means when it looks for “additional grounds”, we need to take a closer look at the decisions where the Committee has spotted a violation.

Synopsis of the Cases Regarding Extradition to Iran

In the group of cases regarding extradition to Iran reviewed during the Committee’s 53rd session, complainants came from very different backgrounds. Despite this, they all managed to strike a chord with the Committee. In X v. Switzerland, the complainant was a university student who helped organize and participated in the 2009 protests against Ahmadinejad’s re-election. He escaped police custody, had his house searched and an arrest warrant was issued against him along with a summons from the Revolutionary Tribunal. In Khademi v. Switzerland, the complainant, who was of Kurdish ethnicity, was a Peshmerga fighter in the armed forces of the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI) for 3 years before resettling elsewhere in Iran. He was summoned and ill-treated by the secret service for allegedly spying for the KDPI and was later sentenced to 15 years of prison after a successful appeal against his death sentence. In Tahmuresi v. Switzerland, the complainant fled Iran after being caught having an affair with a mullah’s wife and eventually assumed leadership positions in Democratic Association for Refugees (Association Démocratique pour les Refugiés – ADR) when in Switzerland. Finally, in Azizi v. Switzerland, the complainant, who was also an ethnic Kurd, actively participated in the political faction of the KDPI, which drew the attention of the authorities and later led him to flee initially to Iraq and later to Switzerland.

Switzerland’s Approach and the Committee’s Stance

Switzerland’s defense in all the given cases had a similar reasoning structure. Switzerland stated that complainants had not brought to the Committee’s attention any new information that was not presented to Swiss judicial authorities. Switzerland further emphasized that although human rights conditions in Iran were worrisome, there was no generalized violence in the country. This was interpreted by Switzerland as a factor that increased the burden of proof of the complainants to show that he or she was in a personal, foreseeable, and real risk of torture upon return to country of origin. Finally, in all the given cases Switzerland stated that leaving Iran illegally was not enough to draw the attention of authorities upon return. After making these points, Switzerland moved on to the specifics of each case in order to show that the complainants’ submissions lacked credibility.

The Committee, in return, rejected all the generic points of defence brought up by Switzerland. It held that the fact that the complainants did not submit any new information that had not already been evaluated by Swiss authorities did not preclude it from examining each case. While examining the human rights conditions in Iran, the Committee heeded the report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, which expressed concern regarding the widespread and systematic use of psychological and physical torture to solicit confessions; incidents of detention and torture of political opponents of the regime and religious minorities; and the fact that Iran frequently administered the death penalty without due process in cases involving certain crimes not meeting international criteria for the most serious offences. These considerations form the foundation of the Committee’s analysis of all the given cases and the nuances in each case led the way for a violation decision.

The Committee’s Groundbreaking Jurisprudence in Relation to Non-Refoulement to Iran

Although the Committee utilized the Special Rapporteur’s report on Iran when evaluating each case, the special conditions in each case further allowed the Committee to set new precedents. To begin with, in Azizi v. Switzerland and Tahmuresi v. Switzerland, the Committee specifically stated that Iran’s lack of ratification of CAT increased concerns since there was no legal option of recourse in case of torture or ill treatment upon return in Iran. Azizi v. Switzerland and Tahmuresi v. Switzerland are the only two cases where the Committee has ever stated such a concern.

Secondly, the Committee specifically addressed the prospect of torture when religious conversion took place in two cases where the complainants converted from Islam to Christianity (Azizi v. Switzerland) or adopted atheistic and agnostic views (X v. Switzerland). Switzerland argued that only active and visible practice of Christianity could draw the Iranian authorities’ attention and did not comment at all in relation to the adoption of atheistic and agnostic views. The Committee, however, ruled that both kinds of conversion from Islam could have serious ramifications in the eyes of the authorities since it would be interpreted as abandonment of Islam, as indicated in the Special Rapporteur’s report. As a result, taking the Committee’s whole jurisprudence into account, Iran is the only country of origin where the Committee has made a judgment on the dangers of extraditing asylum seekers that converted from Islam to other religious or non-religious views.

Lastly, the Committee’s threshold of proof for “high level of political activism” is now much lower when Iran is the country of origin. The Committee stated that taking into consideration the Iranian authorities’ stance against all kinds of opposition as stated in the Special Rapporteur’s report; even low-level political activism could be enough to draw the attention of authorities. The Committee also did not distinguish between having commenced political opposition in Iran (X v. Switzerland) or abroad (Tahmuresi v. Switzerland) as an indicator of vulnerability, stating that a politically inactive person in Iran could just as well attract the authorities’ attention with his/her opposition abroad. In terms of ethnic opposition, Khademi v. Switzerland and Azizi v. Switzerland are the only cases brought against Switzerland regarding the extradition of Iranian nationals with Kurdish ethnicity and the Committee has not distinguished between political opposition in the KDPI and armed opposition as a Peshmerga fighter in the KDPI, considering that both of them are likely to attract the attention of the authorities upon return.

Conclusion

Among the mound of non-refoulement complaints brought against Switzerland, those pertaining to Iran deserve extra attention as these cases account for a significant portion of the given violation decisions. Although, as seen in Chart 2 (below), cases pertaining to extradition to Türkiye have the lead in terms of quantity, Iran is next in line with 10 admissible cases. However, unlike extradition to Türkiye where the Committee has only adopted one violation decision (A.K. v. Switzerland) to date (i.e the 56th session), 8 of the 10 admissible cases regarding extradition to Iran brought against Switzerland were adopted as a violation. These violation decisions are important as they serve as an indicator of a country’s general human rights conditions but also because they concretize how the Committee interprets CAT Article 3 and the General Comment no. 1 regarding Article 3. These cases in particular show that the Committee pays special attention to the reports of the UN Special Procedures and whether a state is a party to the CAT in order to make individual risk assessments.